Neo-Hittite City States

Prepared by Ufuk Önay

College of Social Sciences and Humanities, Koç University

November 2023

This exhibition, prepared within the context of theme “Anatolian Sun: Hittites,” has been curated by utilizing the digitized collection of the Hittitologist Hatice Gonnet-Bağana. Anatolian Sun: Hittites theme aims to approach the Hittite world by different perspectives emphasizing various aspects of the period. The Neo-Hittite City States concept focuses on the aftermath of the collapsed Hittite empire and the following Neo-Hittite city-states, which continue to portray Hittite administrative structure, artistic styles, and Luwian language to some extent in South Anatolia and Northern Syria. This exhibition aims to present an understanding and a narrative of the dynamic social, economic, and administrative structures and their reflection on the cultural plane of the Neo-Hittite city-states through the elements of the Hatice Gonnet-Bağana collection by highlighting the temporality and spatiality throughout the examined period.

Seal of the Neo-Hittite King Kuzi-Teshub

Inventory no. GNT.14.02.sld.01; Map 1, no. 1

Şanlıurfa:

- Lat: 37 15 00 N degrees minutes Lat: 37.2500 decimal degrees

- Long: 039 00 00 E degrees minutes Long: 39.0000 decimal degrees

Following the fall of the Hattusa, Kuzi-Teshub was governing Carchemish as the only heir of the Hittite dynasty (Bryce, 2005/2023, pp. 508, 509). The dynasty founded by Kuzi-Teshub continued to administer Carchemish during the Neo-Hittite period of the city (Bryce, 2012, p. 87). The Neo-Hittite Kingdom of Carchemish was among many principalities that secured significant location, such as mineral-rich areas or river crossings in south-eastern Anatolia and northern Syria. Carchemish was located at the banks of the Euphrates River, according to the Map 1, provided by Thuesen (2002, p. 47), and was particularly notable for continuing Hittite culture, which reflected in their wider usage of Hieroglyphic Hittite script, rather than cuneiform script, as seen in this seal impression of the Neo-Hittite king Kuzi-Teshub from Carchemish. Besides cultural continuity, the “Great King” title was used by the kings of Carchemish and accumulated great wealth among other Neo-Hittite states, which indicates that Carchemishian kings promoted themselves as the only successors of Hittites succeeding Kuzi-Teshu (Bryce, 2005/2023, p. 508).

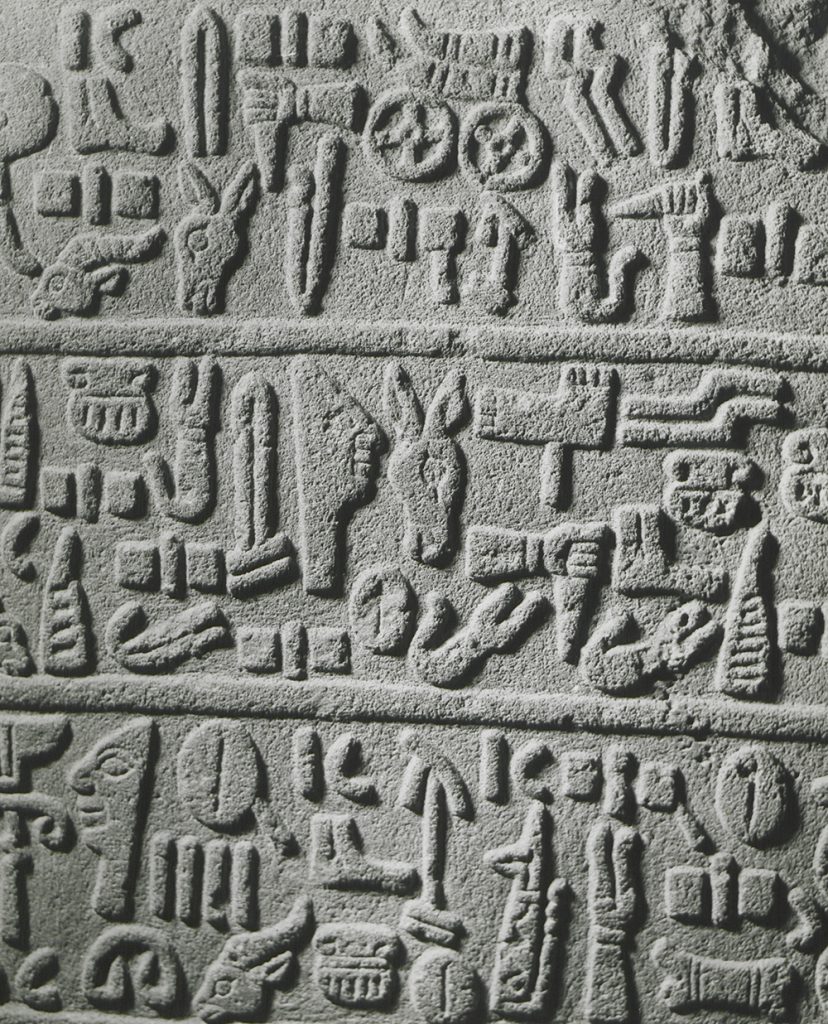

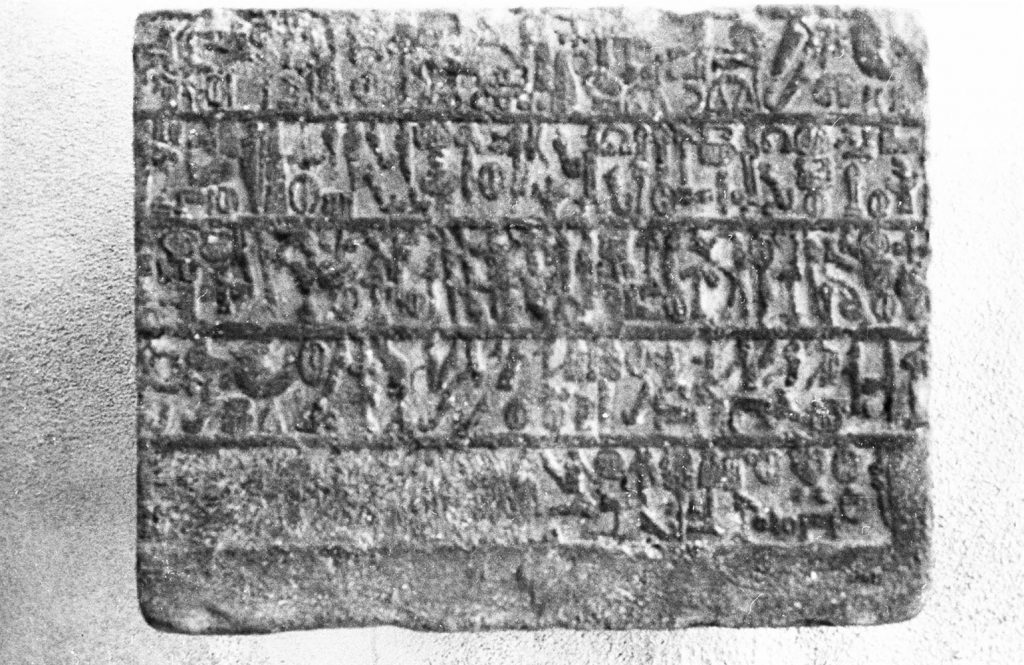

Basalt Slab with neo-Hittite Hieroglyphic Inscription, from Carchemish or Karkemish

Inventory no. GNT.AG.019; Map 1, no. 2

Carchemish (Karkamış):

- Lat: 36 55 00 N degrees minutes Lat: 36.9160 decimal degrees

- Long: 038 00 00 E degrees minutes Long: 38.0000 decimal degrees

This is a Neo-Hittite hieroglyphic inscription found at Carchemish. Carchemish was known for the quality of craftsmanship. Furthermore, the wealth of Carchemish, partly originating from trade and access to raw materials, is reflected in the monumental architecture and wall-reliefs. Consequently, such archaeological evidence from the Hittite and Neo-Hittite periods indicate continuity reached today.

Kubaba Stele, Malatya

Inventory no. GNT.S17.05.phg.05; Map 1, no. 3

Malatya – Arslantepe:

- Lat: 38 34 00 N degrees minutes Lat: 38.5667 decimal degrees

- Long: 037 29 00 E degrees minutes Long: 37.4833 decimal degrees

Kubaba goddess was at the center of varying cults (equivalent of Hepat), particularly around northern Syria and southern Anatolia, spread around the Taurus mountains during the Hittite Empire. Kubaba cult among Neo-Hittite states presents a continuum with the Hittite belief system and, furthermore, presents the cultural continuity in the religious plane. Even though the scholarly opinion is divided on the broader diffusion of the Kubaba cult into Phrygian and Lydian belief systems, one side of the specialists suggest that the Kubaba cult has reflected in Western Anatolian religion, for instance, Albright (1928). Given that the language of Lydians and Phrygians are considered part of the Hittite-Luwian group, it is plausible that religious practices, such as the Kubaba cult, were carried by migrating Neo-Hittites. However, it is significant to note that current academic opinion tends to reject Kubaba’s presence in Lydian and cults.

Neo-Hittite Topada Rock Monument

Inventory no. GNT.S18.18.sld.09; Map 1, no. 4

Acıgöl:

- Lat: 38 33 00 N degrees minutes Lat: 38.5500 decimal degrees

- Long: 034 31 00 E degrees minutes Long: 34.5167 decimal degrees

Topada was held a crucial role within the Neo-Hittite settlement of the Neo-Hittite kingdom of Tapal, thanks to its strategic location and being a prominent military power among its neighbors. Tabal played a significant role in the alliance of Neo-Hittite states against larger Assyria through the end of the 8th century BC. The Topada rock monument mentions a Tabalian king’s conflict with the city of Parzuta; such military events overlap with the militarily prominent position of Tabal among other Neo-Hittite states.

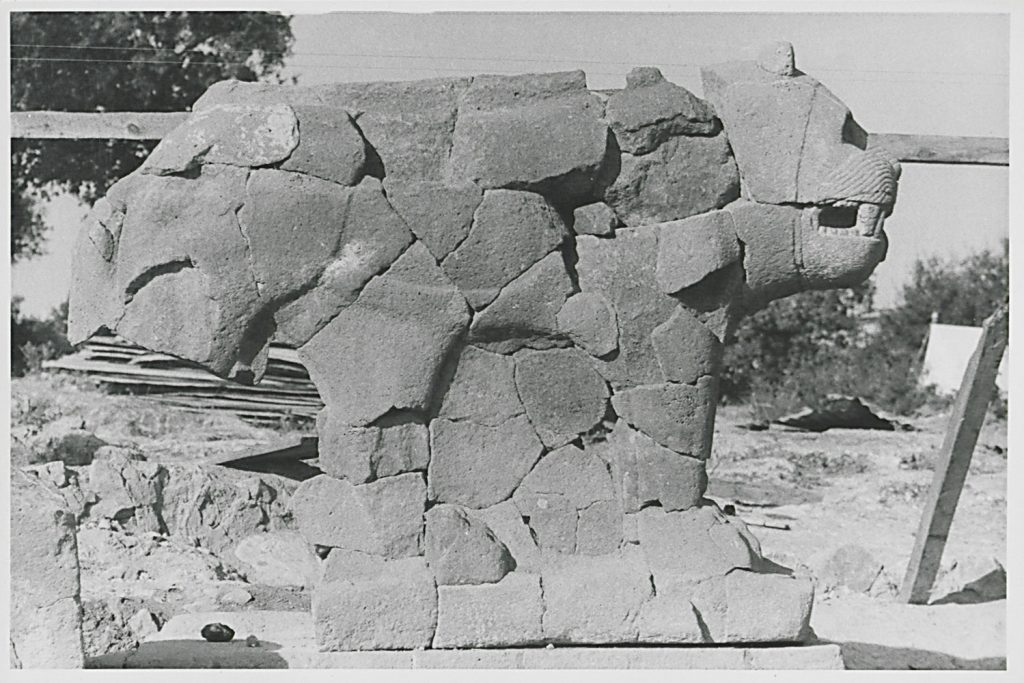

Neo-Hittite Relief from Karatepe

Inventory no. GNT.S20.20.phg.01; Map 1, no. 5

Osmaniye:

- Lat: 37 15 00 N degrees minutes Lat: 37.2500 decimal degrees

- Long: 036 15 00 E degrees minutes Long: 36.2500 decimal degrees

This is a photograph of a Hittite lion from Karatepe from the Neo-Hittite period. The Hittite Lion is one of the distinctive features of the Hittite symbology. For instance, similar lions at the gate of Hattusa are seen as a representative of the Hittite monumental architecture. Such a continuation in the Karatepe site in the Neo-Hittite period elicits the continuity between the Hittite and Neo-Hittite periods. Moreover, as one of the well-documented Neo-Hittite sites, Karatepe, located in the Cilicia region, encapsulates stelae and reliefs that were significant in shedding light on the dark age after the fall of the Hittite empire and deciphering Luwian language used extensively by presumably Luwian populations of the Neo-Hittite city-states.

Neo-Hittite period, Midas Monument

Inventory no. GNT.S06.20.phg.01; Map 1, no. 6

Eskişehir:

- Lat: 39 40 00 N degrees minutes Lat: 39.6667 decimal degrees

- Long: 031 10 00 E degrees minutes Long: 31.1667 decimal degrees

This Neo-Hittite relief found in Yazılıkaya, Hattausa, is related to the question of the degree of the connection between the Neo-Hittite states and Phrygians. Phrygians were in Anatolia during Neo-Hittite states and coexisted with Muski (Bryce, 2005/2023, p. 515). As Bryce (2005/2023, p. 516) mediated from Muscarella (1989), Mita of Muski, as seen in Assyrian sources, was probably the King Midas. Particularly, King Mita sought to form an alliance with the Neo-Hittite state Carchemish; nevertheless, Carchemish and Mita failed against Assyrians as Carchemish was “absorbed”, as the concept employed by Bryce (2012, pp. 5, 44, 146), by Assyria (Bryce, 2012, p. 98). Another possible explanation presented by Macqueen (1975/2010) suggests that the Phrygian king Midas might have been referred as Mita of Muski. According to the mentioned explanation by Macqueen (1975/2010), there is a direct connection between Neo-Hittite cities and Phrygians. “Midas City” (Yazılıkaya), accommodating one main monument and numerous scripts, is presented among the most important archeological evidence for the Phrygian presence in the region (Bryce, 2012, p. 42). This stele being described as Neo-Hittite supports such a narrative. Moreover, such a reconstruction of 8th-century West Anatolian history can change the accepted route of the northwest in which Phrygians entered Anatolia in favor of the southeast, where Neo-Hittite states were located.

Hunting Scene on the Neo-Hittite Pottery

Map 1, no. 7

Yeşilhisar (Niğde):

- Lat: 38 21 00 N degrees minutes Lat: 38.3500 decimal degrees

- Long: 035 06 00 E degrees minutes Long: 35.1000 decimal degrees

Neo-Hittite pottery had a distinctive style known as “Phrygian”. The naming of such pottery style further presents the connection between Neo-Hittites and Phrygian. This pottery in the Hatice Gonnet Collection presents distinctive features of and animal representations of Phrygian pottery, based on the pottery example provided in Macqueen (1975/2010). Various similarities among the aforementioned two Indo-European speaking communities, such as the naming of Neo-Hittite pottery style, can be justified by the valuation of Neo-Hittite archeological evidence based on well-known Phrygian styles rather than a chronological juxtaposition.

Lion Sculpture from Tell Ta’jinat

Inventory no. GNT.S03.13.ngv.03; Map 1, no. 8

Tell Ta’yinat:

- Lat: 36 14 51 N degrees minutes Lat: 36.2470 decimal degrees

- Long: 036 22 35 E degrees minutes Long: 36.3760 decimal degrees

Lion sculptures were removed from the gate of Tell Tayinat, believed to be the capital of Patina Kingdom, also known as Unqi. Due to its strategic proximity to cedar sources and passages in Mount Amanus, Patina Kingdom was a significant Neo-Hittite state. Within the historical context, the Patina Kingdom was engaged in conflicts against expanding Assyrians in 878 BC and, furthermore, participated in an alliance of Neo-Hittite states in 857 BC partly due to Luwian roots of the administrative elite of the state. The historical evidence of Luwian connections to the city is reflected in the artistic style of lion sculptures, which present similarities to Hittite lion sculptures. Moreover, such symbology reflected into the lion sculptures has spread among Neo-Hittite states. For instance, aforementioned lion from Karatepe is an example of the wider utilization of the mentioned iconography.

Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscription Fragments from Hama

Inventory no. GNT.S03.18.ngv.02; Map 1, no. 9

Hamāh:

- Lat: 35 09 00 N degrees minutes Lat: 35.1500 decimal degrees

- Long: 036 44 00 E degrees minutes Long: 36.7333 decimal degrees

This is a photograph of the “Hieroglyphic Luwian inscription fragments from Hama.” Hama was ruled by Aramean kings, which is a distinctive feature of the kingdom in contrast to other Neo-Hittite kingdoms ruled by Luwian rulers following the end of the Hittite empire. Furthermore, the utilization of Hittite wall inscriptions in building walls indicates a separation of Hama from the Hittite identity. However, the mentioned archeological evidence should be evaluated within the greater context of the monumental features of the city. The gate lions at the entrance of Hama display partial continuity with the Hittite culture. Therefore, it can be presumed, according to the evidence, that the identity of Hama changed over time with a significant Aramaean presence in the region.

Basalt Relief Fragment from Zincirli

Map 1, no. 10

Zincirli (Sam’al):

- Lat: 37 10 36 N degrees minutes Lat: 37.1036 decimal degrees

- Long: 036 67 58 E degrees minutes Long: 36.6758 decimal degrees

This is a photograph of a basalt relief fragment from Zincirli, the capital of Sam’al. Similar to Hama, as mentioned earlier, Sam’al, as a state, differentiated itself from Neo-Hittite states due to the ethnic background of its rulers; because they were Aramean. However, the architectural style in this settlement is partly similar to Hittites and presents some connection to Hittite culture.

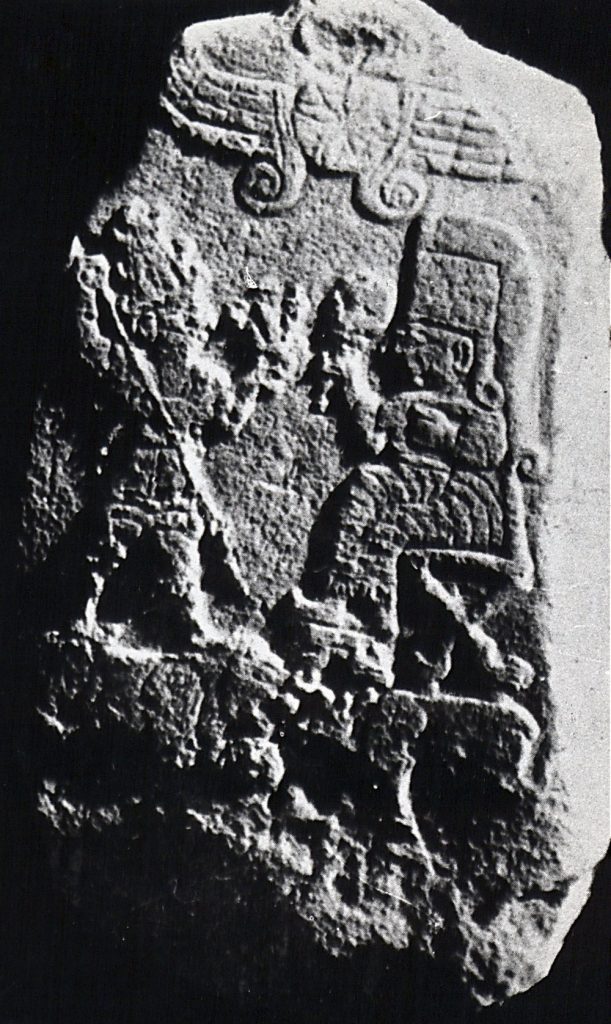

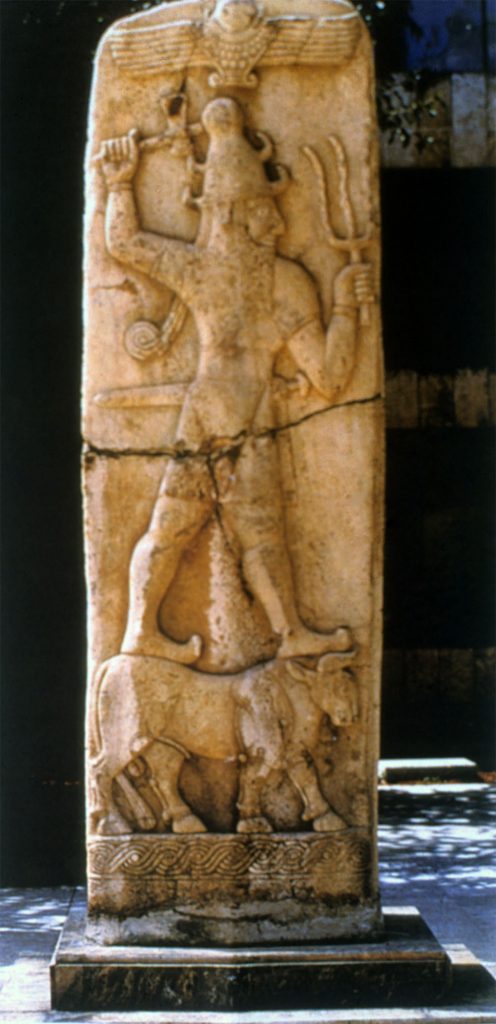

Tell Ahmar II, the Ahmar/Qubbah Hittite Stele Storm-God

Inventory no. GNT.S03.25.phg.02; Map 1, no. 11

Tell Ahmar (archaeological site):

- Lat: 36 08 00 N degrees minutes Lat: 36.1330 decimal degrees

- Long: 037 34 00 E degrees minutes Long: 37.5760 decimal degrees

This is the second stele excavated from Til-Barsib, which accommodated rulers of Bit-Adini. These stelae are in Hittite Hieroglyphic script and dedicated to weather god. By employing such archeological and linguistic evidence, Ussishkin (1971) moves to the question of whether Bit-Adini was a Neo-Hittite or Aramean city-state. Ussishkin (1971, p. 431) answers the aforementioned question by the concept and the period of “Aramaean-ization,” which was placed before the Neo-Hittite period. Furthermore, by mediating Hawkins (1995), Thuesen (2002) supports Ussishkin’s (1971) periodization, mentioning an Aramaean period before the Neo-Hittie dynasty of Masuwari. Therefore, Bit-Adini, particularly during the Masuwari period, presents disparity against the current periodization of various Neo-Hittite city-states.

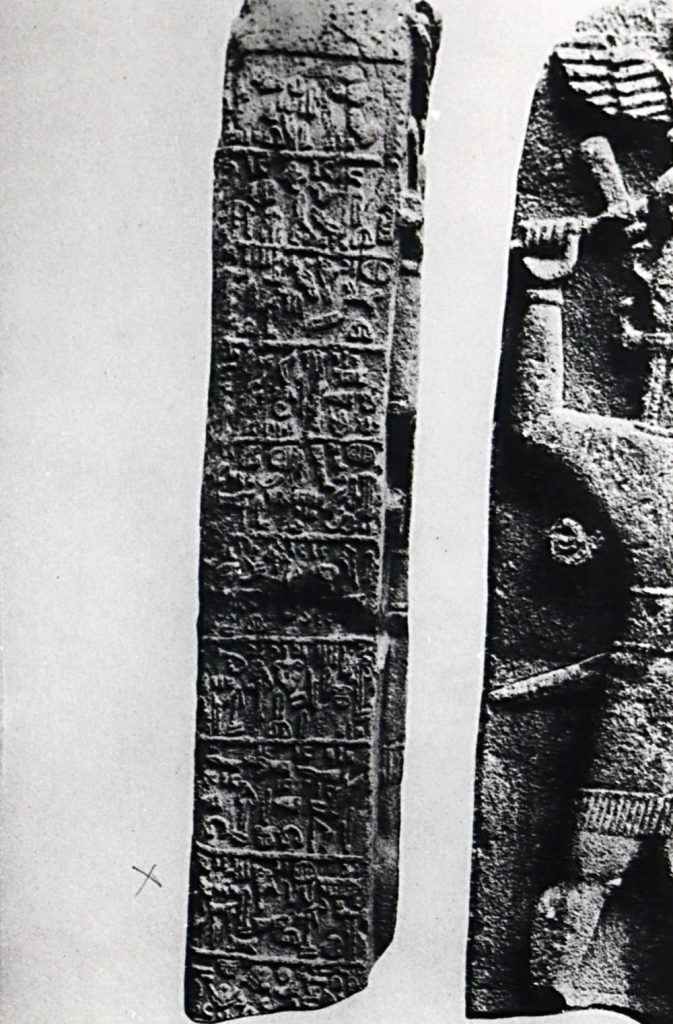

Tell Ahmar Stele 1, dedicated to the Storm God

Inventory no. GNT.S03.26.phg.72; Map 1, no. 12

Tell Ahmar (archaeological site):

- Lat: 36 08 00 N degrees minutes Lat: 36.1330 decimal degrees

- Long: 037 34 00 E degrees minutes Long: 37.5760 decimal degrees

This is the photograph of the first stele found at Tell Ahmar dedicated to the weather god preceding the second stele. There are stylistic and linguistic similarities between the two stelae as both stelae present Hittite hieroglyphic inscriptions.

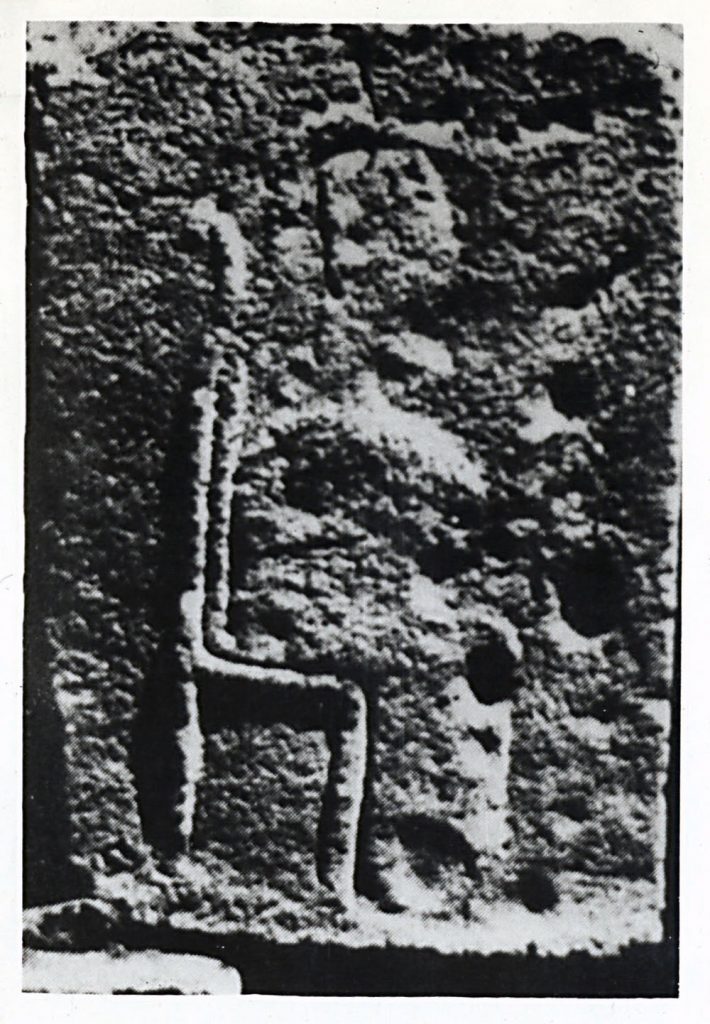

Tell Ahmar VI, the Ahmar/Qubbah Hittite stele for Storm God dedicated by king of Masuwari (Til-Barsib)

Inventory no. GNT.S03.24.sld.01; Map 1, no. 13

Aleppo:

- Lat: 36 12 03 N degrees minutes Lat: 36.2012 decimal degrees

- Long: 037 09 39 E degrees minutes Long: 37.1612 decimal degrees

This is the photograph of the sixth Tell Ahmar stele with a note of “Tell-Ahmar 6,” presumably by Hatice Gonnet-Bağana herself. This stele displays the storm god, which can be perceived as identical to the weather god, as mentioned by Ussishkin (1971) and Thuesen (2002) in the previous stelae. In this relief of the weather god carving, artistic features that are similar to Hittite iconography are visible, such as the posture and beard of the weather god. Furthermore, the representation of the ox beneath the weather god supports the similarity of symbolism employed by Hittites and Bit-Adini, which may be seen as evidence for the Neo-Hittite period of the city and for the extent of the connection between the two cultures.

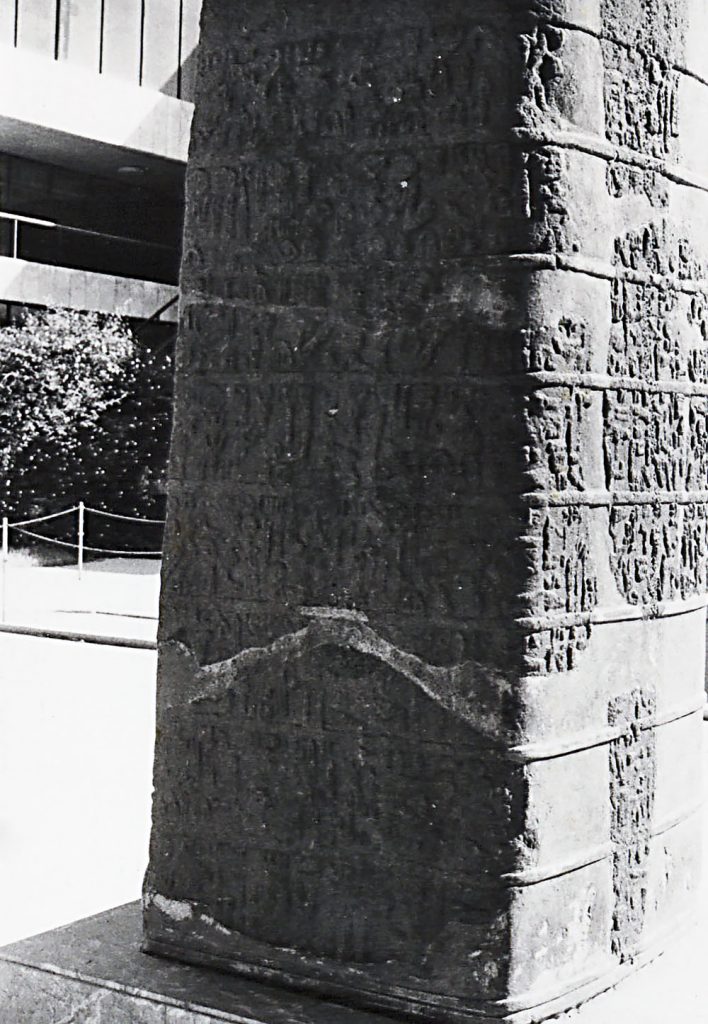

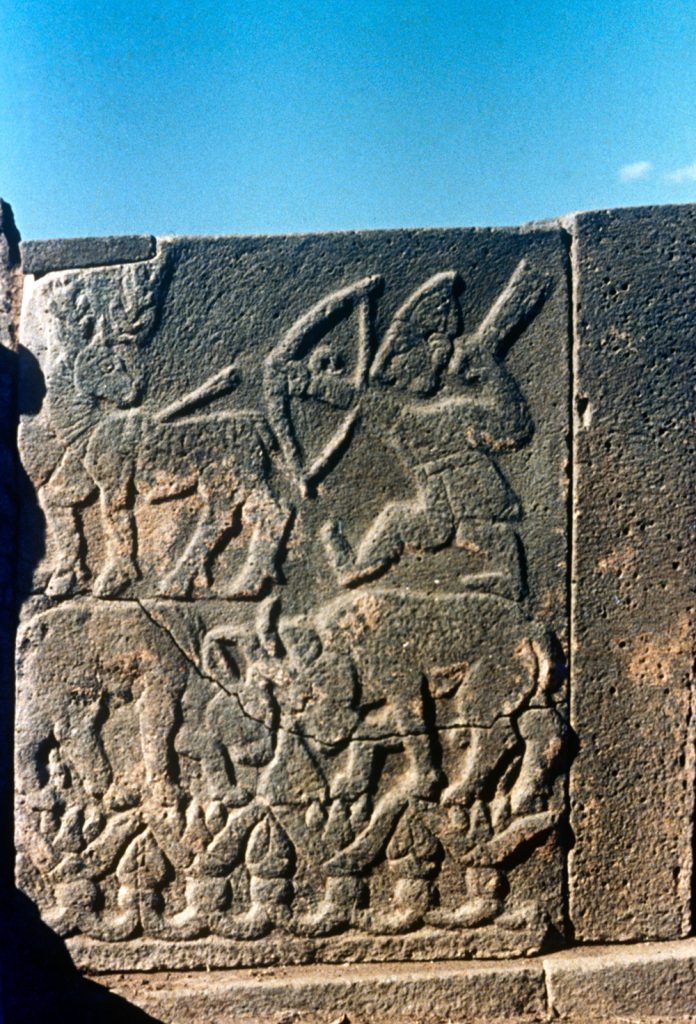

Neo-Hittite Relief, Karatepe

Inventory no. GNT.S20.29.sld.11; Map 1, no. 14

Osmaniye:

- Lat: 37 15 00 N degrees minutes Lat: 37.2500 decimal degrees

- Long: 036 15 00 E degrees minutes Long: 36.2500 decimal degrees

The photograph displays a bilingual Neo-Hittite relief found in the Neo-Hitit fortress of Karatepe, located within the borders of Osmaniye province. The relief features inscriptions in both Phrygian and Luwian languages. The text on the reliefs elaborates on the economic and administrative developments of the region, consequently contributing to the legitimization of the ruler. Furthermore, these reliefs from Karatepe provide significant information on the economic activity in the region of Cilicia. The importance of the maritime trade in the Cilicia region reflected in Karatepe relieves. Such a vivid maritime trade may have attracted Assyrians to the north, which may have eventually increased the Assyrian pressure on the region, as trade routes were an element of determining expansion throughout the Hittite and Neo-Hittite periods.

Neo-Hittite Relief, Karatepe, King and his guards

Inventory no. GNT.S20.10.phg.02; Map 1, no. 15

Osmaniye:

- Lat: 37 15 00 N degrees minutes Lat: 37.2500 decimal degrees

- Long: 036 15 00 E degrees minutes Long: 36.2500 decimal degrees

Conclusion

The Neo-Hittite period spanning from the collapse of the Hittite empire on the eve of the 12th century BC until the expansion of the Assyrian influence in 8th century. Through the related archeological and linguistic evidence Neo-Hittite city states elicit dynamic nature of migration movements, trade connections, and political developments of the period. The Luwian hieroglyphic script and partial continuation of the Hittite symbolism in monumental and civic architecture constitutes a portion of archeological and linguistic evidence. The Hatice Gonnet-Bağana Collection present photographs of a variety of elements from period which are used in this exhibition and reflects the complexity and dynamism of the period.

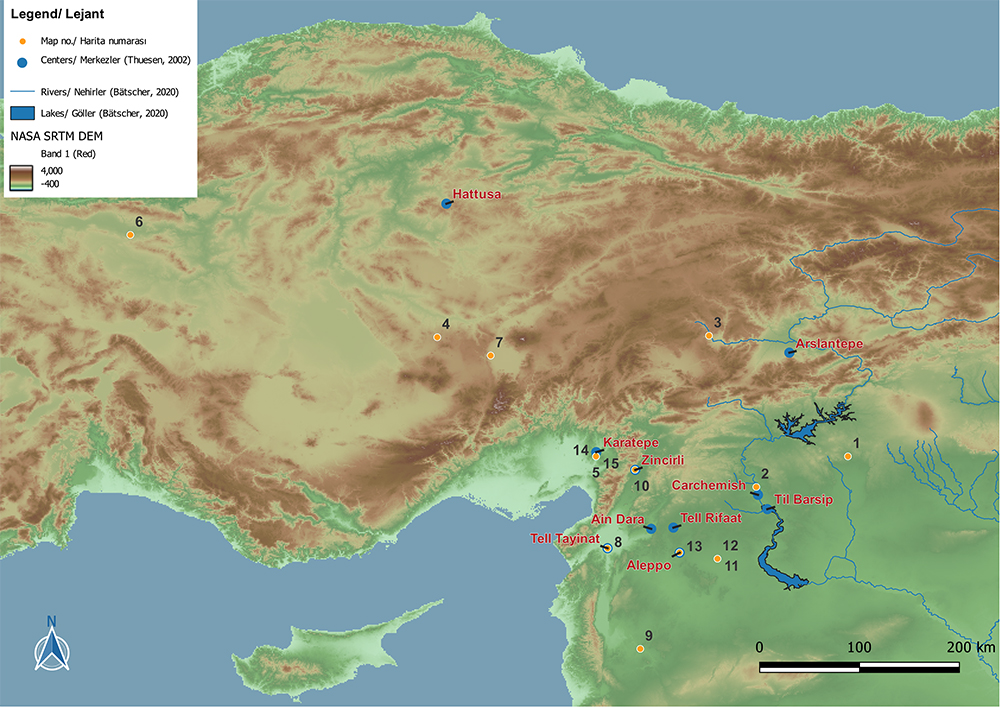

Map 1: Digital Exhibition Elements

This map presents the location of noteworthy centers of the Neo-Hittite period, c.10th to 8th century BC, based on Figure 1 in Thuesen (2002, p. 47) and the locations of the exhibition elements through the spatial data provided by SKL. The maps are prepared using Geographical Information Systems (GIS), particularly QGIS, a widely used GIS software. This map is based on the 201 merged digital elevation models (DEMs) from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) conducted by NASA JPL (2013), dataset provided by (NASA JPL, 2013). Merged DEMs are colorized according to their representation power decided by the author. Figure one in Thuesen (2002, p. 47) is georeferenced by linear transformation. River systems formed around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers are included in the map to present the dispersion of Neo-Hittite settlements around water bodies; the data for rivers and lakes are provided by Bätscher (2020). Furthermore, some of the significant regions or settlement names are included in this map. Such a representation of spatial data in different can be acknowledged within the concept of “spatial analysis” as different layes of data visualize the examined material, as the concept used in Schuurman (2006, pp. 3,4).

Map 2: Neo Hittite Kingdoms

This map illustrates the locations of the Late Hittite kingdoms and the Kızıldağ region, an area with limited documentation, based on the descriptions provided in Alparslan (2009, pp. 137-148). It is superimposed on a base map consistent with the previous version and relies on the 201 merged digital elevation model (DEM) from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) provided by NASA JPL (2013) and its corresponding dataset (NASA JPL, 2013). The archaeological sites (SYM) were subsequently color-coded using the same color scheme as the one used in the “Digital Exhibition Elements” map. Additionally, the river systems around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers were incorporated into the map using the dataset prepared by Bätscher (2020).

References

Albright, W. F. (1928). The Anatolian Goddess Kubaba. Archiv Für Orientforschung, 5, 229-231. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41680188

Aro, S. (2013). Carchemish Before and After 1200 BC. In A. Mouton, A., I. Rutherford & I. Yakubovich (Eds.). Luwian Identities: Culture, Language and Religion Between Anatolia and the Aegean.Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004253414_013

Bryce, T. (2023). The Kingdom of The Hittites (İ. Kutluk, Trans.). Alfa Basım Yayım (Original work published in 2005).

Bryce, T. (2012). The World of The Neo-Hittite Kingdoms: A Political and Military History. Oxford University Press.

Doğan-Alparslan, M. (2009). Geç Hitit Devletleri. In M. Alparslan, Hititolojiye Giriş, TEBE.

Hawkins, J. D. (1995). The Political Geography of North Syria and South-east Anatolia in the Neo-Assyrian Period. In M. Liverani (ed.), Neo-Assyrian Geography. 87-101.

Hawkins J. D. (2000). Corpus of Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions. Walter de Gruyter.

Gelb, I. J. (1939). Hittite Hieroglyphic Monuments. OIP, 45. 1939. The University of Chicago Press.

Hrozný, B. (1933-1937). Les Inscriptions Hittites Hiéroglyphiques. 480-490.

Lovejoy, N., & Matessi, A. (2023). Kubaba and other Divine Ladies of the Syro-Anatolian Iron Age: Developmental Trajectories, Local Variations, and Interregional Interactions. In L. Warbinek, F. Giusfredi (ed. by), Theonyms, Panthea and Syncretisms in Hittite Anatolia and Northern Syria. Proceedings of the TeAI Workshop Held in Verona, March 25-26, 2022, Studia Asiana 14, 109-126.

Macqueen, J. G. (2010). The Hittites and Their Contemporaries in Asia (revised and enlarged edition). Thames and Hudson. (Original work published 1975).

Meriggi, P. (1935). Sur deux inscriptions en hiéroglyphes hittites de Tell Ahmar. Revue Hittite et Asianique, Année 1935, 45-57.

Muscarella, O. W. (1989). King Midas of and the Greeks. Fs Özgüç. 333-344.

Pınarcık, P. (2018). Geç Hitit Dönemi’nde Toroslardan Amanoslara Uzanan Bölgedeki Ekonomik Faaliyetler. Belleten 82, 383-406. doi:10.37879/belleten.2018.383

Thuesen, I. (2002). The Neo-Hittite City-states. In M. H. Hansen (Ed.), A Comparative Study of Six City-State Cultures: An Investigation (pp. 43-55). Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. Historisk-filosofiske skrifter No. 27.

Ussishkin, D. (1971). Was Bit-Adini a Neo-Hittite or Aramaean State? Orientalia, 40(4), 431-437. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43078965

Voigt, M. M., & Henrickson, R. C. (2000). Formation of the Phrygian State: The Early Iron Age at Gordion. Anatolian Studies 50, 37-54.

Yıldırım N. (2016). Çiviyazılı Kaynaklara Göre Patina Krallığın’dan Unqi Krallığı’na Antakya ve Amik Ovası’nın Tarihsel Süreci. Belleten, 80, 701-718. doi:10.37879/belleten.2016.701

Map 1

Map 1: Digital Exhibition Elements

This map presents the location of noteworthy centers of the Neo-Hittite period, c.10th to 8th century BC, based on Figure 1 in Thuesen (2002, p. 47) and the locations of the exhibition elements through the spatial data provided by SKL. The maps are prepared using Geographical Information Systems (GIS), particularly QGIS, a widely used GIS software. This map is based on the 201 merged digital elevation models (DEMs) from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) conducted by NASA JPL (2013), dataset provided by (NASA JPL, 2013). Merged DEMs are colorized according to their representation power decided by the author. Figure one in Thuesen (2002, p. 47) is georeferenced by linear transformation. River systems formed around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers are included in the map to present the dispersion of Neo-Hittite settlements around water bodies; the data for rivers and lakes are provided by Bätscher (2020). Furthermore, some of the significant regions or settlement names are included in this map. Such a representation of spatial data in different can be acknowledged within the concept of “spatial analysis” as different layes of data visualize the examined material, as the concept used in Schuurman (2006, pp. 3,4).

Map 2

Map 2: Neo Hittite Kingdoms

This map illustrates the locations of the Late Hittite kingdoms and the Kızıldağ region, an area with limited documentation, based on the descriptions provided in Alparslan (2009, pp. 137-148). It is superimposed on a base map consistent with the previous version and relies on the 201 merged digital elevation model (DEM) from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) provided by NASA JPL (2013) and its corresponding dataset (NASA JPL, 2013). The archaeological sites (SYM) were subsequently color-coded using the same color scheme as the one used in the “Digital Exhibition Elements” map. Additionally, the river systems around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers were incorporated into the map using the dataset prepared by Bätscher (2020).

References

Albright, W. F. (1928). The Anatolian Goddess Kubaba. Archiv Für Orientforschung, 5, 229-231. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41680188

Aro, S. (2013). Carchemish Before and After 1200 BC. In A. Mouton, A., I. Rutherford & I. Yakubovich (Eds.). Luwian Identities: Culture, Language and Religion Between Anatolia and the Aegean.Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004253414_013

Bryce, T. (2023). The Kingdom of The Hittites (İ. Kutluk, Trans.). Alfa Basım Yayım (Original work published in 2005).

Bryce, T. (2012). The World of The Neo-Hittite Kingdoms: A Political and Military History. Oxford University Press.

Doğan-Alparslan, M. (2009). Geç Hitit Devletleri. In M. Alparslan, Hititolojiye Giriş, TEBE.

Hawkins, J. D. (1995). The Political Geography of North Syria and South-east Anatolia in the Neo-Assyrian Period. In M. Liverani (ed.), Neo-Assyrian Geography. 87-101.

Hawkins J. D. (2000). Corpus of Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions. Walter de Gruyter.

Gelb, I. J. (1939). Hittite Hieroglyphic Monuments. OIP, 45. 1939. The University of Chicago Press.

Hrozný, B. (1933-1937). Les Inscriptions Hittites Hiéroglyphiques. 480-490.

Lovejoy, N., & Matessi, A. (2023). Kubaba and other Divine Ladies of the Syro-Anatolian Iron Age: Developmental Trajectories, Local Variations, and Interregional Interactions. In L. Warbinek, F. Giusfredi (ed. by), Theonyms, Panthea and Syncretisms in Hittite Anatolia and Northern Syria. Proceedings of the TeAI Workshop Held in Verona, March 25-26, 2022, Studia Asiana 14, 109-126.

Macqueen, J. G. (2010). The Hittites and Their Contemporaries in Asia (revised and enlarged edition). Thames and Hudson. (Original work published 1975).

Meriggi, P. (1935). Sur deux inscriptions en hiéroglyphes hittites de Tell Ahmar. Revue Hittite et Asianique, Année 1935, 45-57.

Muscarella, O. W. (1989). King Midas of and the Greeks. Fs Özgüç. 333-344.

Pınarcık, P. (2018). Geç Hitit Dönemi’nde Toroslardan Amanoslara Uzanan Bölgedeki Ekonomik Faaliyetler. Belleten 82, 383-406. doi:10.37879/belleten.2018.383

Thuesen, I. (2002). The Neo-Hittite City-states. In M. H. Hansen (Ed.), A Comparative Study of Six City-State Cultures: An Investigation (pp. 43-55). Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. Historisk-filosofiske skrifter No. 27.

Ussishkin, D. (1971). Was Bit-Adini a Neo-Hittite or Aramaean State? Orientalia, 40(4), 431-437. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43078965

Voigt, M. M., & Henrickson, R. C. (2000). Formation of the Phrygian State: The Early Iron Age at Gordion. Anatolian Studies 50, 37-54.

Yıldırım N. (2016). Çiviyazılı Kaynaklara Göre Patina Krallığın’dan Unqi Krallığı’na Antakya ve Amik Ovası’nın Tarihsel Süreci. Belleten, 80, 701-718. doi:10.37879/belleten.2016.701